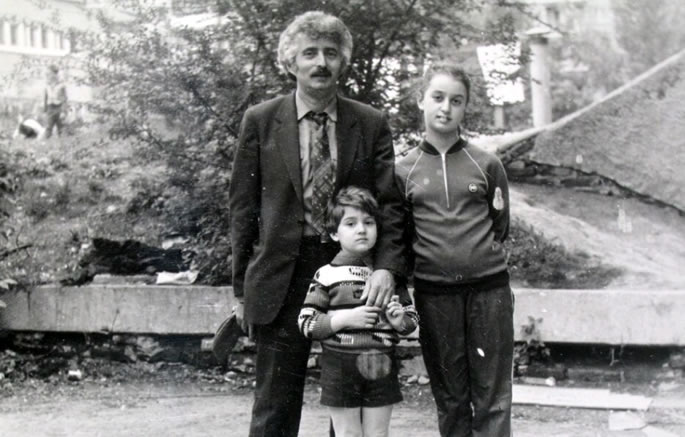

These days, as we stay at home, many of us are feeling a wide range of emotions, including anxiety over the future and resentment about being “stuck” inside. While I shift between these paradigms, I think back to the time my family left our home in Saratov in the Soviet Union on Sept. 14, 1989.

Walking out of the only place I knew into a completely unknown future at 12 years of age was overwhelming, to say the least. And before we could call America our new home, we lived as stateless refugees in two camps in Austria and Italy.

Our journey began with a train to Moscow and a flight to Vienna. We had two suitcases per person with basic clothes and some food. From Vienna’s airport, we were loaded onto buses and taken to a tiny motel in the mountains, where 99 of us were housed in a place built for a maximum of 33 guests.

We were placed with another family—a total of 14 people—in a motel room with two queen-size beds. Women and children slept on the beds, perpendicular to its length, in order to accomodate more people. Men slept on the floor.

The most challenging part was the kitchen, with just one refrigerator and a single stove. None of us had the money to order prepared food, so we cooked simple, affordable dishes of potatoes, pasta, eggs and soup. The stove was used around the clock, 24 hours a day. Each family had about an hour to cook for the next day. Space in the refrigerator was split to a few inches per family.

Once, my grandmother added too much pepper to our pot of soup because she was in such a hurry to finish while the next family counted the minutes. I was so hungry … but the soup was unbearably spicy, and I couldn’t manage more than a spoonful. That day, my brother and I ate only bread.

At one point, the town was celebrating harvest day. Wagons filled with grapes drove through the main street. People were singing and throwing fruit at us, the bystanders. I never ate so many grapes in my life! They were sweet as honey and even when I could not swallow one more, my parents saved some for days afterwards. It was wonderful to have extra food.

After about a month, we were transferred to a small coastal town in Italy called Ladispoli. For security reasons, the train didn’t fully stop at the station, so the men had no choice but to throw suitcases into each other’s arms, creating a human conveyor belt. People were helping each other, fearful of losing their only possessions. Together with my brother, I jumped onto the station platform from the slow-moving train.

Sometimes, I wonder if people who say that possessions are meaningless are the ones who have them in abundance and have no idea what life is like without them.

Before our forefather Jacob met his brother Esau after decades of separation, he returned to the other side of the stream to recover a few small vessels he had left behind.1 Why would Jacob be mindful of such a minor loss? Perhaps the Torah is teaching us that we are here to elevate our world, not transcend it. Jacob knew this, and he took responsibility for all his earthly possessions. Everything we own is a gift from our loving Creator; everything has a purpose. Jacob’s actions teach us to appreciate what we have and view our resources as purposeful and meaningful.

When we arrived in Italy in October of 1989, we needed to find a place to live. This was challenging because hundreds of refugees were tasked with the same mission. We went knocking on doors and pleading affittasi appartamenti: “Is the apartment available for rent?” After hours of walking, suitcases in hand, a refugee family finally agreed to sublet us a room in the house they had rented.

We were seven people with one queen-size bed. Again, women and children slept on the bed, and men on the floor. The house wasn’t heated; I was always cold. I was exhausted and anxious over our unknown future, anticipating our entrance visas to the United States.

It’s hard to explain the effect this journey had on our emotional, physical and psychological resources. Lying in bed next to my mother and grandmother, I couldn’t fall asleep for hours, dreaming of my own bed. I imagined a warm, cozy and safe home with a kitchen filled with sweets. Years later, I realized that my dreams were based only on what I knew. Isn’t it interesting how we are only capable of dreaming up things that are “possible” based on the past?

Yet G‑d has a way of surprising us beyond our wildest dreams. I would never have believed that my home now would have more than one bathroom, an electric stove, a walk-in closet and a heated blanket. These were things I didn’t even know existed.

After two long and cold months of waiting, we were finally notified that the American government had issued our entry visas. This was a special day. Our journey was finally coming to an end.

The trip to Rome’s international airport was scheduled twice a week—on Sundays and Thursdays. Our plane departed early Tuesday morning, on Nov. 14, so we needed to take the transport on Sunday. We spent two long and grueling days in the airport. We were completely spent in every possible way. I remember crying to my parents that I wanted to go home. I will never forget what it is like to have no home. Never.

Ever since that day in September of 1989 when we walked out of our apartment in Saratov, I gained a completely new appreciation of what “home” represents.

It is a safe, warm place with comfortable couches, cozy blankets, the smell of a clean bed, kitchen cabinets and a refrigerator filled with food, curtains on the windows and walls decorated with family pictures.

Years later, a few important pieces were added to my description of an ideal dwelling, such as a mezuzah on the doorpost, Shabbat candles, and that special feeling of peacefulness on Friday nights.

As the coronavirus epidemic continues to keep us inside, let’s appreciate the value of everything that home holds. Let’s not take for granted the fact that we have our own private world behind those front doors. Everything that we have is a gift, and gratitude is the most beautiful decoration of any household.

The light of gratitude and mindfulness holds the power to illuminate even the world outside and bring the world to its higher, G‑dly consciousness.

May this happen soon.