“Remember that in a hall of perfect darkness, if you light one small candle, its precious light will be seen from afar, by everyone.”

— The Lubavitcher Rebbe to Benjamin Netanyahu about his work at the United Nations

Lev Furman was born in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, in 1947. His father, Mikhail, was a Soviet naval officer and his mother, Bella, a nurse. Despite Soviet prohibitions, Lev had a brit milah, a circumcision, at eight days old, as required by Jewish law. When Lev was 12, his father found a teacher, a Chabad chassid named Avraham Abu, to teach his son basic Jewish ideas. This was a very dangerous decision, as it was considered a stance against the Communist government, which prohibited any religious observance. These secret lessons lasted for a few months before Lev turned 13.

Lev experienced a Passover Seder in 1970. While this was not yet a fully kosher celebration, it was symbolic of hope and freedom. In 1973, upon Lev’s release from his mandatory year of military service, the Furman family applied for exit visas to immigrate to Israel. Unfortunately, their request was denied, and the family became known as refuseniks (people who were refused permission to leave the USSR). Being a refusenik was an unofficial life sentence in the Soviet Union; it meant losing jobs and being considered a social outcast by the Soviets. Desperate to earn a living for the family, Lev, an engineer, found a job as a stoker (coal burner), which no skilled worker would be interested in.

Lev wasn’t discouraged by his dismal employment and spent his free time learning Hebrew, eventually becoming a teacher. He also became actively involved with other refuseniks, sharing information and receiving secret packages of religious articles from Israel, Europe and the United States. Such packages included prayer books, Hebrew textbooks, literature about Israel and religious items.

In 1974, Lev’s life changed forever when he met a fellow refusenik, Yitzchak Kogan, later commonly known as the “tzaddik (‘righteous person’) of Leningrad.”

Yitzchak came from an observant family. His maternal grandfather, Yossef Tamarkin, was close to the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, and Yitzchak was connected to the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. Lev and Yitzchak became close friends, and the Kogan family introduced Lev to their Jewish lifestyle and religious traditions, which in the Soviet Union was a rarity. Around that time, Lev received his first tallit as a gift from the West, along with a magazine called Vozrazdenie, “Revival”. Lev often jeopardized his own safety, eager to help Yitzchak and his wife Sofa with their work on behalf of the Soviet Jews.

While fighting for his freedom, Lev traveled to major Soviet cities, teaching Judaism to the Jewish youth of the country. In 1976, he participated in a Purim shpiel (play), playing the role of Haman. He and other refuseniks went on tour, traveling from Leningrad to Moscow to perform it.

In 1977, Lev’s father was arrested for supporting his son’s defiance of the Soviet regime and jailed for 10 days. Lev himself was arrested three months later and jailed for a 15-day period. After his release, he continued to teach Hebrew and help Yitzchak Kogan with his work.

In 1978, Lev joined the Kogan family and 50 other guests for his first real kosher Seder. Two years later, Lev began to keep kosher and observe Shabbat. This was a very challenging commitment in the Soviet Union. Jews had no kosher meat in Leningrad until Yitzchak learned how to do shechitah, kosher slaughtering, and later became a shochet for the entire Soviet Union.

The years 1983 and 1984 were particularly challenging for Lev with many confrontations with the KGB and Soviet police. Lev was often followed and harassed for minor incidents. For example, one day a policeman suddenly appeared when Lev crossed a street at a red light. Two witnesses were generally required to make an arrest. Suddenly, witnesses appeared out of nowhere, clearly strategically planted to offer testimony. Many similar situations were staged to make life particularly difficult for the Furman family.

Searches were often made by the KGB agents. Lev recalls that “Mama had a weak heart. She was completely overwhelmed by these challenges of our fight for freedom. One day, police came with a search warrant and Mama couldn’t get up from her bed. She was so sick. It was horrible.”

Lev remembers how one day Yitzchak asked if Lev was a firstborn son. He was surprised by this inquiry, but Yitzchak explained that there is a ritual called the “redemption of the firstborn son” or pidyon haben. Through this mitzvah, a Jewish firstborn is “redeemed” by a priest 30 days after he is born. Yitzchak insisted that Lev should undergo the pidyon haben ceremony despite his age, explaining to Lev that he himself was a kohen and thus could perform this ritual. All that was necessary was a silver item, so Lev brought an old silver spoon for this occasion. Lev still cannot fully comprehend the miraculous outcome of that ceremony. Right after he took part in it, the confrontations, searches and arrests stopped.

“The Kogan family taught me so much about my heritage,” says Lev. “I was overjoyed when, in 1987, their family finally received visas to immigrate to Israel. Right before their departure, I met my wife, Marina, at a goodbye party of fellow refuseniks who finally received their exit visas.

“We married two months later under a chuppah. Marina was originally from Kiev. She had been a refusenik since 1979. Her story was much more complicated than mine, because she was not only emotionally tormented but suffered physical confrontations for five years before we met. Right before our initial encounter, Marina wrote a letter, explaining all the abuse she and her mother endured since they applied to immigrate to Israel. I used my connections to the West and sent it to England, where it was broadcast by the BBC. After that international act of defiance, our situation became even more dangerous.

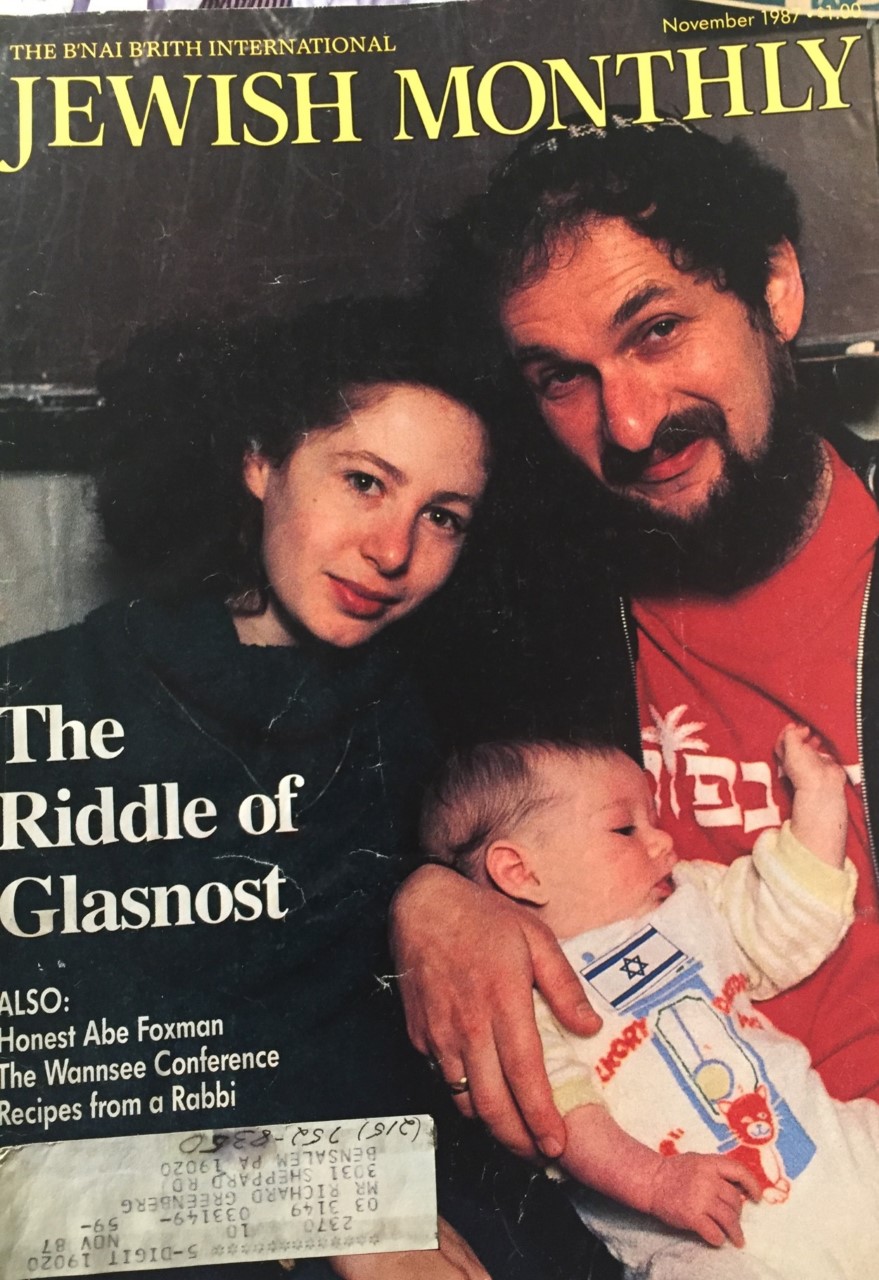

“When Marina was pregnant, the KGB agents made us aware that if we did not give up our fight, neither Marina nor our future child would survive the labor. We hired a doctor, trying to prevent any “accidents,” yet when, on March 6, 1987, my wife went into labor, this doctor never arrived to work. I am still in shock from the events of that day. Later, I learned that while Marina was in labor, someone injected her with an unknown medication. She remembers “floating away.” This might have been the end, yet G‑d intervened on our behalf, and a hospital department head, who was unaware of the KGB plot, miraculously walked into her room after hearing her screaming and ultimately saved two lives. Since no visitors, including husbands, were allowed in Soviet labor and delivery hospitals, I learned about this incident over a very brief phone conversation with Marina. To say that I was horrified was an understatement.

“That day, I wrote a message to my wife on the wall directly opposite her window: ‘Marina, you are my hero.’

“Years later, we tried to find this doctor to thank him for what he did, but unfortunately, he was fired immediately after the incident, and we never had a chance to see him again. We named our baby girl Aliyah, hoping that she would be a living testament to the strength of the Jewish people. The Soviet government didn’t want to register this name, yet once again we protested and continued our fight for freedom.”

In 1987, during the “Let My People Go” rally in Washington, D.C., the Furmans joined half a million protestors on the other side of the ocean in Palace Square, the site of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, where the Furmans held up their handmade posters of their refusenik status. Unsurprisingly, they had been followed by KGB agents and were immediately arrested, along with their baby daughter.

At the police station, Marina and Lev were separated from their baby, and they heard her scream in another room. Lev was jailed for 10 days and released on the first day of Chanukah. On the last day of the holiday, the Furmans experienced a Chanukah miracle: They received their exit visas to finally immigrate to Israel!

They landed in Israel on the country’s Independence Day, watching fireworks from the plane. For them, it was their personal Independence Day.

The Furman family was greeted by many refuseniks and friends from around the world. It was particularly meaningful and joyous for Lev to be reunited with Yitzchak Kogan.

Sofa Kogan gave simple advice to Marina: “In the Soviet Union, you learned how to survive. Here in Israel, you need to learn how to live.”

The Furmans often think about these profound words. Life went on, and in 1994, the family welcomed their second daughter, Michal, named after Lev’s father. Lev found a job as a Hebrew teacher, working with new immigrants. Marina worked for the United Jewish Appeal, eventually becoming the main speaker for the organization, traveling the world and advocating for the Land of Israel.

Yitzchak Kogan continued his work on behalf of the Jewish people. He followed the guidance of the Lubavitcher Rebbe and was given the task to evacuate Jewish children from Chernobyl after the nuclear explosion. Yitzchak facilitated the dramatic airlift of Jewish children from the danger zone to Israel.

Eventually, the Kogan family returned to the former Soviet Union under the direction of the Rebbe to rebuild Judaism after the fall of communism. They were sent to Moscow, where Yitzchak became the chief rabbi at the Bolshaya Bronnaya Synagogue in Moscow.

In 2001, Lev and Marina visited Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, for the first time since their immigration. In an emotional reunion, Lev visited Yitzchak in Moscow. While the streets and the surroundings looked the same, the two friends met in a completely different reality. They were no longer prisoners of communism. They had won their battle, just like the Maccabees in the story of Chanukah. May their legacy be a blessing upon our Nation.

The ‘Refuseniks’ Who Refused to Compromise on their Jewish Values – Contemporary Voices (chabad.org)